Tribal nations pre-date the formation of the United States and governed themselves for millennia before European settlers occupied the lands. Nearly 200 years after the United States started negotiating treaties with Tribal nations, Tribal governments started taking back control and decision-making authority over the programs that serve their citizens and communities.

Treaty-Making

The United States negotiated hundreds of treaties on a nation-to-nation basis with Tribal governments. Prior to the Treaty-Making, Tribal governments were self-ruling sovereigns.

For example, the Treaty of Perpetual Friendship between the United States and the Choctaw Nation calls for “the Government and people of the United States are hereby obliged to secure to the said Choctaw Nation of Red People the jurisdiction and government of all the persons and property that may be within their limits west, so that no Territory or State shall ever have a right to pass laws for the government of the Choctaw Nation and their descendants…”

Bureau of Indian Affairs Created

Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, without special congressional authorization, set up a “Bureau of Indian Affairs” within his department and assigned the duties of the office to Thomas L. McKenney. McKenney held the office until dismissed by President Jackson in 1830. Congress confirmed the position, then designated “Commissioner of Indian Affairs,” in 1832.

Worcester v. Georgia

“… the settled doctrine of the law of nations is, that a weaker power does not surrender its independence—its right to self-government, by associating with a stronger, and taking its protection. A weak state, in order to provide for its safety, may place itself under the protection of one more powerful, without stripping itself of the right of government, and ceasing to be a state.

BIA Transfers to the Department of the Interior

BIA was transferred from the War Department to the Department of the Interior.

Secretary of the Interior Annual Report from 1869 Acknowledging Tribal Right to Self-Rule

Excerpt from the Annual Report of the Secretary of the Interior:

“The associated tribes, of which the Cherokees have taken the lead, are those best fitted for a fuller experiment in self-government. They are already familiar with most of the forms of executive, legislative, and judicial action in use among us, and I believe them well prepared to dispense with the tutelage of our agents, if they may have a delegate of their own upon the floor of the House of Representatives to speak for them. Representation chosen by the tribes themselves, and responsible to themselves, is the only mode of making the country acquainted with their condition and with our obligations to them.”

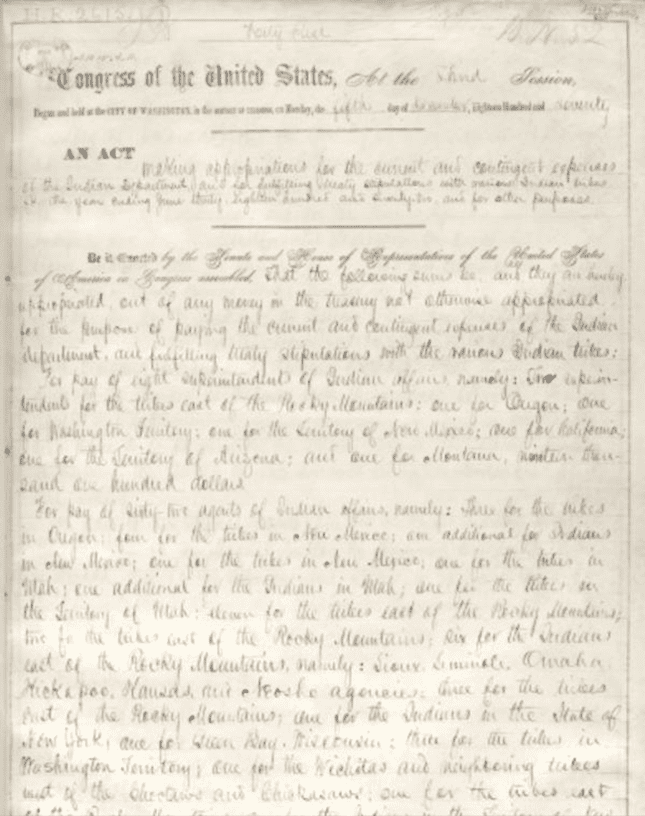

United States Ends Treaty Negotiations

1871 Appropriations Act:

Ceased the ratification of treaties with Tribal nations and declared Congress has the sole governing power to make laws controlling the lives of Tribal governments and their citizens.

Congress Limits Tribal Powers

Major Crimes Act:

Gave federal courts jurisdiction over the crimes of murder, manslaughter, rape, assault with intent to kill, arson, burglary, and larceny when committed by Native Americans.

Supreme Court Erodes Tribal Powers

The United States v. Kagama:

“The Constitution of the United States is almost silent in regard to the relations of the government which was established by it to the numerous tribes of Indians within its borders.” Nonetheless, the Court reasoned that tribal governments “owe all their powers to the statutes of the United States conferring on them the powers which they exercise, and which are liable to be withdrawn, modified, or repealed at any time by Congress”

Powers of Self-Government are Not Subject to the Requirements of the U.S. Constitution

Talton v. Mays:

The sovereign rights of the Cherokee Nation were created long before the United States Constitution was drafted, and these rights are recognized by treaty. The self-governance powers of the Cherokee Nation are therefore independent of the United States Constitution. The authority of Congress to regulate the actions of Indian nations has no bearing on the origins of the Cherokee Nation’s powers of self-governance.

Congress Provides Explicit Authorization for Indian Programs

Snyder Act:

The law provided the BIA with explicit authorization for much of the activities that the agency was already undertaking. It also authorized the employment of physicians to serve Indian tribes. Prior to the Snyder Act, Congress had made detailed annual appropriations for these BIA activities, but funds were not always appropriated because these activities lacked explicit authorization.

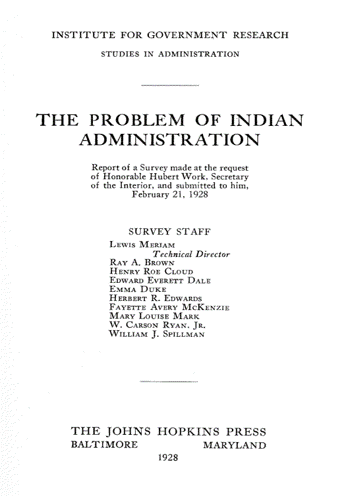

Problems with Paternalism Identified

Meriam Report:

Found that paternalism was not effective for Tribal nations and made recommendations for administrative and legislative actions to move away from paternalism to eventual Indian self-determination.

Indian Reorganization Act (IRA)

The IRA ended the allotment of Tribal land, authorized the Secretary of the Interior to take land into trust, recognized Tribal governments, and encouraged Tribes to adopt constitutions. The Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act extended the IRA provisions to Tribal nations located within the boundaries of Oklahoma. The Alaska Indian Reorganization Act extended the IRA provisions to Tribal nations located within the boundaries of Alaska.

Note: Some Tribal constitutions approved under the IRA grant Tribal powers to the United States or state governments. For example, some Tribal constitutions convey control over tribal membership to the US Congress, grant criminal law powers to the state, grant veto power over tribal legislation to the Secretary of the Interior, or require Secretarial approval for amendments to the tribal constitution.

Felix Cohen Shares Thoughts on the Meaning of Self-Governance

“Not all who speak of Self-Government mean the same thing by the term. Therefore, let me say at the outset that by Self-Government I mean that form of government in which decisions are made not by the people who are wisest or ablest or closest to some throne in Washington or in Heaven, but rather by the people who are most directly affected by the decisions. Self-Government is not a new or radical idea. Rather, it is one of the oldest staple ingredients of the American way of life. Many Indians in this country enjoyed Self-Government long before European immigrants who came to these shores did.”

Congress Seeks to Terminate Tribal Governments Status as Nations

House Concurrent Resolution 108:

A termination era policy seen as destroying tribal institutions, as in effect depriving Indian people of their status as nations, and forcing them to assimilate individually into the larger social-political society.

Federal programs, such as relocation, devastate Tribal communities as individuals and families are relocated from reservations to big cities. Federal officials make efforts to assimilate relocated individuals.

BIA video explaining the relocation program.

DOI video teaching relocated Tribal citizens telephone etiquette.

Indian Health Care Programs Moved to the Public Health Service

The Indian Health Facilities Act transferred the responsibility for Indian health care from the BIA to the Public Health Service (PHS) in the then newly established Department of Health, Education and Welfare (now the Department of Health and Human Services).

Tribal Rights to Self-Determination Start to Gain More Attention

An American Indian Conference held at the University of Chicago allowed citizens of all Native nations to voice their opinions and desires. The proceedings of the conference contain proposed legislative and regulatory changes to alleviate problems of the Indian population in economic development, health, welfare, housing, law, enforcement and education.

“We are not pleading for special treatment at the hands of the American people. When we ask that our treaties be respected… the right of self-government, a right which the Indians possessed before the coming of the white man, has never been extinguished; indeed, it has been repeatedly sustained by the courts of the United States. Our leaders made binding agreements—ceding lands as requested by the United States; keeping the peace; harboring no enemies of the nation. And the people stood with the leaders in accepting these obligations. A treaty, in the minds of our people, is an eternal word.”

President Johnson’s “Forgotten American” Message

“I propose a new goal for our Indian programs: A goal that ends the old debate about “termination” of Indian programs and stresses self-determination; a goal that erases old attitudes of paternalism and promotes partnership self-help.”

Johnson’s Community Action Program Provides Opportunity for Tribal Governments to Administer Federal Resources

One of the first opportunities for Tribal governments to have a say in the implementation of federal programs came about as a result of Johnson’s Community Action Program. This program was authorized by the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 with the goals of fighting poverty on a local level through a massive infusion of federal funds. Tribal governments and organizations were eligible to receive funds and this was also the first time Tribes were not dependent on BIA for the implementation of federal assistance programs.

The success of programs run by Tribal governments under the program demonstrated that Tribes could develop and administer successful programs.

“..for the first time, tribes can plan and run their own programs for their people without someone in the BIA dictating to them.”

–Vine Deloria Jr.

President Nixon’s Special Message to Congress

“Because termination is morally and legally unacceptable, because it produces bad practical results, and because the mere threat of termination tends to discourage self-sufficiency among Indian groups, I am asking the Congress to pass a new Concurrent Resolution which would expressly renounce, repudiate and repeal the termination policy. . . . Self-determination among the Indian people can and must be encouraged without the threat of eventual termination. In my view, in fact, that is the only way that self-determination can be effectively fostered.”

Tribal Governments Pursue Contracts to Administer Federal Programs

In 1970, the Miccosukee Tribe presented the BIA a proposal to contract for services provided by the BIA’s Miccosukee Agency, School, and related activities.

The Associate Solicitor for Indian Affairs initially declined the contract proposal based on the view that the BIA lacked legal authority to enter into the contract. After several rounds of negotiations among the Tribe, the Solicitor’s Office, and the Appropriations Committees of the House and Senate, it was determined that the Tribe could create a private corporation with which the BIA could contract for services.

At each turn in its negotiation with the BIA, the Tribe was confronted with objections to the specific contents of its contract proposal. In short, the experience of the Miccosukee Tribe demonstrated that the BIA’s efforts to move forward with self-determination were hampered by existing legal authority.

Specific legislation was necessary to bring to fruition the emerging concept of self-determination.

Federal Policy of Termination Reversed

Senate Concurrent Resolution 26:

Reversed the federal policy of termination and develop a government-wide commitment to enable Indians to determine their own future.

Special Legal Status of Indians

Morton v. Mancari:

The preferential hiring of Indians for BIA positions was challenged by non-Indian employees, who claimed that the Indian preference law of 1934 had been repealed by the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972. The Supreme Court, overturning a district court decision, supported the preference policy and declared that the preference was based not on “racial discrimination” but on the special legal status of the Indians.

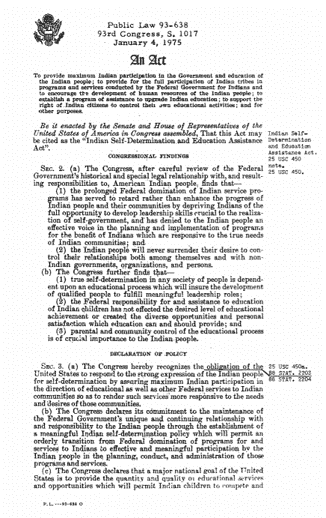

ISDEAA Increases Tribal Choice in the Delivery of Federal Programs

Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act:

An Act to provide maximum Indian participation in the Government and education of the Indian people; to provide for the full participation of Indian tribes in programs and services conducted by the Federal Government for Indians and to encourage the development of human resources of the Indian people; to establish a program of assistance to upgrade Indian education; to support the right of Indian citizens to control their own educational activities; and for other purposes.

Provides an option for “Indian tribes” and “tribal organizations” to enter a self-determination contract to take over the management of certain programs, or portions thereof, that were previously administered by the Indian Health Service and the Department of the Interior.

Indian Healthcare Improvement Act

“it is the policy of the Nation, in fulfillment of its special trust responsibilities and legal obligations to Indians to ensure the highest possible health status for Indians and urban Indians and to provide all the resources necessary to effect that policy….”

Authorized many specific IHS activities, sets out the national policy for health services administered to Indians, and set health condition goals for the IHS service population. Authorized collections from Medicare, Medicaid, and other third-party insurers.

GAO Report: The Indian Self-Determination Act- Many Obstacles Remain

“Federal domination over the Indian programs and services of the BIA and IHS has changed little since the enactment 2 years ago of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act. The act allows more than is presently being done, but Tribal and Federal officials have cited many obstacles that inhibit their initiatives, policies and activities on Indian self-determination.”

“The Amendment is intended to insure that Congress’ original intent in passing the Indian Self-Determination Act is successfully implemented. The Act states that it would “permit an orderly transition from Federal domination of programs for and services to Indians to effective and meaningful participation by the Indian people in the planning, conduct and administration of those programs and services. Since the Act was passed in 1975 and the regulations published over 1 1/2 years ago, Indian people throughout the Nation have encountered problems and barriers to the assumption of control over the Bureau of Indian Affairs and Indian Health Service Programs. The Senate Committee on Indian Affairs conducted oversight hearings to investigate these problems with the implementation of Public 93-638, one of our hearings, held in Albuquerque, New Mexico, generated testimony from over 30 Indian Tribes and Tribal organizations. On the basis of Indian testimony and information gathered directly from IHS and BIA, it became clear that the intent of Congress has been frustrated because there has been no meaningful transfer of control in the actual implementation of the Act. Rather, control has been retained by the agencies through a combination of factors.”

United States v. Wheeler

“Although physically within the territory of the United States and subject to ultimate federal control, they [Indian Tribes] nonetheless remain “a separate people, with the power of regulating their internal and social relations.” . . . Their right of internal self-government includes the right to prescribe laws applicable to tribe members and to enforce those laws by criminal sanctions…”

Presidential Commission on Reservation Economies

Called for a transfer of administrative functions and funds from the BIA to Tribal governments to improve tribal self-sufficiency, reduce BIA bureaucracy, and improve the general welfare of Native Americans.

GAO Report: Contracting for Health Services under ISDEAA

“Indian self-determination has not been achieved, according to the majority of Indian contractors GAO visited and the majority responding to GAO’S questionnaire. Indian contractors perceive the law as giving them the opportunity to determine for themselves the manner in which health care services should be delivered, and they see IHS restricting this freedom by various contract regulations.”

Alliance of American Indian Leaders

Formed in 1986 in direct response to the deteriorating Federal-Tribal relationship. Proposed a Self-Governance Demonstration Project to Congress.

The Arizona Republic Publishes Articles Dealing with Corruption and Misuse of Funds in BIA

Hear more about the role of the Arizona Republic articles in furthering Self-Governance.

“It is hard to designate by title the subject of this hearing. It could be called by the headline in the articles that I am sure the Secretary has received and Mr. Swimmer has received. It could be called “Fraud in Indian Country, A Billion-Dollar Betrayal,” or it could be called, “The State of the BIA and What Should Be Done About It.” I suppose it could be called any number of other things, but the fact remains that there is a condition out in Indian country that has been described in the articles of the Arizona Republic.”

Ross Swimmer, AS-IA, proposed to Congress that BIA transfer all resources, at all levels, to any tribal government interested in such a transfer—includes a provision absolving the US of its trust responsibilities to any tribal government that accepts the transfer of funds (Section 209). The Alliance of American Indian Leaders did not support Swimmer’s proposal and provided Appropriations Committee with draft legislation to implement a “tribal self-governance demonstration project” that would NOT abolish trust responsibilities.

Hear more about the Demonstration Project proposal.

Clarifies intent of PL 93-638 in attempt to address concerns with Title I.

Adds Title II – ensures tribes’ sovereign immunity from suit and ensures trust responsibility is not terminated.

Adds Title III – establishes a 5-year self-governance demonstration project within DOI and expands the type of programs and functions tribal governments can take over, minimizes oversight by federal agencies, maximizes flexibility for tribal governments to redesign and reallocate.

Learn more about these amendments.

President Joe DeLaCruz, Quinault Nation, Gives Speech Titled “Indian Self-Determination, the Ideal, and Indian Self-Governance, the Reality”

This Compact is to carry out an unprecedented Self-Governance Demonstration Project, authorized by Title III, P.L. 100-472, which is intended as an experiment in the areas of planning, funding and program operations within the Government-to-Government relationship between Indian Tribes and the United States. The Demonstration Project encourages experimentation in order to determine how to improve this Government-to-Government Relationship and promote the perpetuation of the Tribe.

Cherokee Nation Begins Negotiating Self-Governance Agreement

“I believe the Cherokee Nation stands at a crossroads. It is time for us to reflect on where we have been and think about where we want to go… We have come full circle from being a totally independent and sovereign nation to a point where the federal government attempted to dissolve our powers of self-government. Now we again have the opportunity to fully exercise our rights of self-government.” – Principal Chief Wilma Mankiller

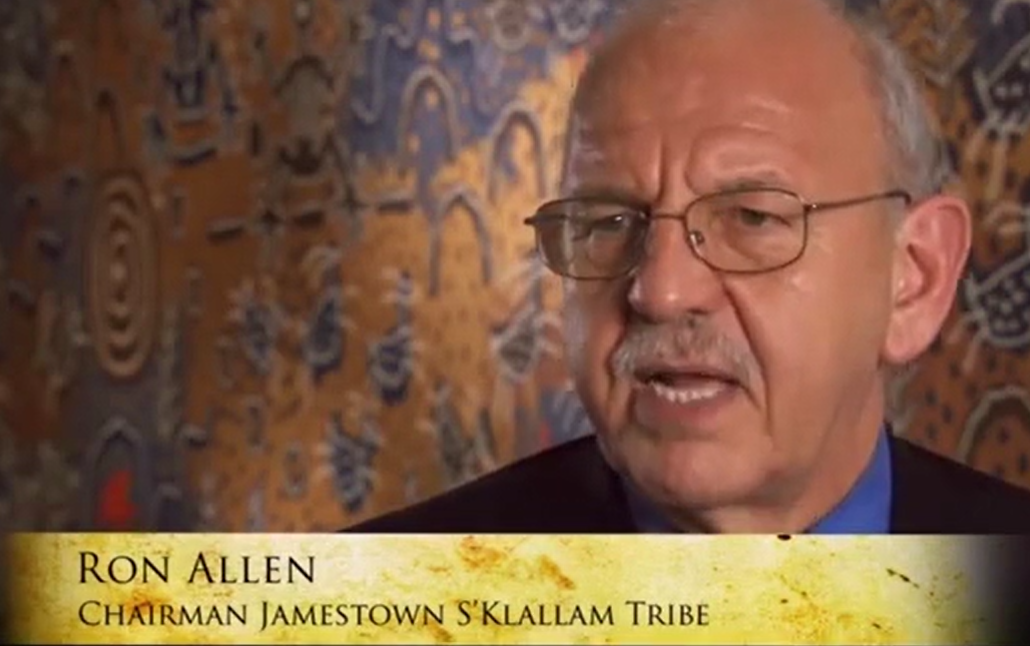

Baseline Measures Task Force

The enabling legislation for the Tribal Self -Governance Demonstration Project contained requirements for semi-annual reports to Congress concerning the relative costs and benefits of the Tribal Self -Governance Demonstration Project based on mutually determined baseline measurements. In order to meet this obligation, several of the Compacts of Self-Governance (Lummi, Hoopa, Jamestown Sklallam, Cherokee, Mille Lacs, and Quinauit) contained language which addressed the need for establishing baseline measures. Several of the Compacts called for the establishment of a Baseline Measures Task Force which included Tribal representation, Interior representation, and academic representation. The Task Force met in October, November, and December of 1990 with recommendations from the Task Force to be presented to Designated Officials by January 15, 1991.

National Indian Forest Resources Management Act

Sec. 305. Management of Indian forest land. (a) Management Activities.—The Secretary shall undertake forest land management activities on Indian forest land, either directly or through contracts, cooperative agreements, or grants under the Indian Self-Determination Act (25 U.S.C. 450 et seq.).

Tribal Self-Governance Demonstration Project Act

Extends the Demonstration Project within DOI for 3 years Increases number of tribes that can participate in the demonstration project to 30 Requires HHS to study feasibility of extending a demonstration project to IHS Waives the statute requiring Secretarial approval of attorney and professional service contracts.

“Trying a New Way” Study

Independent Assessment Report on the Self-Governance Demonstration Project by the Center for the Study of American Indian Law and Policy, University of Oklahoma

Established the IHS Tribal Self-Governance Demonstration Project. The first IHS Demonstration Project agreements were signed on September 30,1993

“The Congress hereby declares that it is the policy of this Nation, in fulfillment of its special responsibilities and legal obligation to the American Indian people, to assure the highest possible health status for Indians and urban Indians and to provide all resources necessary to effect that policy.”

Congress Declares the Tribal Self-Governance Demonstration Project a Success

Senate Report 103-205:

“The Federal policy of Tribal Self-Governance was conceived and nurtured by Indian Tribes and their able leaders. It is a policy seasoned by experience and matured by time. In the Committee’s view, it is now time to make Tribal Self-Governance a permanent part of all Department of the Interior policy and action relating to those Indian Tribes who choose to participate.”

“Today’s hearing will focus on the implementation of the Self-governance Demonstration Project Act by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Indian Health Service. We will discuss some of the obstacles as well as some of the successes of the project since its enactment in 1988.

For the past 2 days, a number of the self-governance tribes have been meeting here in Washington, DC to discuss establishing the project on a permanent basis. To assist with those deliberations, I provide the tribes with a draft bill that would make the program permanent for the Department of the Interior with the full intention of including the Indian Health Service at a later date.

I would be interested in any comments the tribes might have on this draft bill as well as your own ideas on what should be included in permanent legislation. I believe this project has been a success and deserves to be established as a permanent option for all tribes.”

Extends the IHS Tribal Self-Governance Demonstration Project to 18 years and authorizes the establishment of Self-Governance Tribal Advisory Committees.

Establishes Title IV, making Self-Governance a permanent tribal option within DOI.

Makes amendments to Title I- Mandatory “model agreement” & Access to Central Office Admin funds.

Requires DOI to develop a list of non-BIA programs eligible for compacting.

Congressional Hearing: Oversight of IHS’ Implementation of the Tribal Self-Governance Act

“It appears that the implementation by tribes of health-related self-governance efforts has been largely successful. It also appears that much more remains to be done by IHS to remove Federal obstacles to full implementation by tribes.”

White Earth Nation Pursues Self-Governance Agreement

“The advantage of self-governance will be less Bureau red tape, and the flexibility of the tribe to put the money where it’s needed most.”

Statement of Representative Don Young: The consistent failure of Federal agencies (IHS and BIA) to fully fund – contract support costs has resulted in financial management problems for tribes as they struggle to pay for federally mandated annual single-agency audits, liability insurance, financial management systems, personnel salaries, property management and other administrative costs. Congress must remember that tribes are operating Federal programs and are carrying out Federal responsibilities when they operate self-determination contracts. Tribes, in some instances, have had to resort to using their own financial resources to subsidize contract support costs. It is the Committees’ belief, and the House and Senate Interior Appropriations Committees’ belief that tribes should not be forced to use their own financial resources to subsidize Federal contract support costs.

Tribal Self-Governance Amendments of 2000

Establishes Title V, making self-governance a permanent for tribal option within IHS Makes amendments to Title I Establishes Title VI- requires HHS to study the feasibility of extending self-governance options to non-IHS agencies within HHS.

Navajo Nation v. Department of Health and Human Services

Addresses whether an Indian tribe may administer TANF through a self-determination contract under the ISDEAA. TANF does not qualify as a contractable program under the ISDEAA.

Cherokee Nation v. Leavitt

The Supreme Court found that ISDEAA agreements are similar to government procurement contracts and, as such, they bind agencies to honor the payment terms where agencies possess sufficient unrestricted appropriated funds to meet those terms.

Susanville Indian Rancheria v. Leavitt

IHS rejected the Tribe’s final offer under Title V because the Tribe proposed to charge pharmacy service beneficiaries a small co-pay. IHS provided no funding for pharmacy services, and the Tribe determined that without the user fees, the Tribe would be unable to provide such services at all. IHS took the position that the Tribe could not charge beneficiaries because the agency itself cannot do so, despite the plain language of the controlling Title V provision: “The Indian Health Service under this sub-chapter shall neither bill nor charge those Indians who may have the economic means to pay for services, nor require any Indian tribe to do so.” The court held that this provision clearly did not prevent the Tribe from charging; it prevented IHS from requiring the Tribe to charge.

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

Reauthorized IHCIA permanently and indefinitely; expanded IHS activities to include long-term care services, created a continuum of behavioral health and treatment services, and expanded the ability of ITs and TOs to receive reimbursements directly from Medicare and Medicaid.

Salazar v. Ramah Navajo Chapter

ISDEAA directs the Secretary of the Interior to enter into contracts with willing tribes, pursuant to which those tribes will provide services such as education and law enforcement that otherwise would have been provided by the Federal Government. ISDA mandates that the Secretary shall pay the full amount of “contract support costs” incurred by tribes in performing their contracts. At issue in this case is whether the Government must pay those costs when Congress appropriates sufficient funds to pay in full any individual contractor’s contract support costs, but not enough funds to cover the aggregate amount due every contractor. Consistent with longstanding principles of Government contracting law, we hold that the Government must pay each tribe’s contract support costs in full.

Helping Expedite and Advance Responsible Tribal Home Ownership Act of 2012

The HEARTH Act enabled tribal self-government by authorizing federally recognized tribes to issue leases of restricted Indian lands for residential, business, agriculture, wind, and solar use without the approval of the Secretary of the Interior if such leases are executed under tribal regulations that have been approved by the Secretary.

HHS Self-Governance Tribal Federal Workgroup – Final Report

Title VI of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (ISDEAA)

required the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to determine the feasibility of a demonstration

project extending Tribal Self-Governance to HHS agencies other than the Indian Health Service (IHS). In 2003, HHS submitted a report to the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs and the House Natural Resources Committee that a Self-Governance demonstration project was feasible. In 2011, HHS revived the effort and established the Self-Governance Tribal-Federal Workgroup (SGTFW) and issued a Final Report in September.

The Report concluded that there is no existing authority that would permit a demonstration project of the sort proposed by the 2003 feasibility study which could be carried out under Title VI of the ISDEAA without specific legislative authority from Congress.

Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe v. Burwell

The Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe submitted a contract proposal to the Secretary of Health and Human Services under the Act for funding to operate an emergency medical services (EMS) program that the Indian Health Service (IHS) had been funding directly since 1993. After receiving the Tribe’s proposal, the Secretary discontinued the EMS program, which IHS viewed as financially untenable, and denied the Tribe’s request on the ground that the agency would not have funded the program going forward. The Tribe brought suit and has moved for summary judgment, arguing that the Secretary lacked authority to deny the proposal. The Court agreed.

Once the Secretary receives a valid proposal to assume the operation an ongoing program, the Act requires her to accept the proposal unless one or more enumerated declination criteria are met. Because she did not rest her decision on any of those criteria, denying the Tribe’s proposal violated the Act. The Court will therefore grant summary judgment in favor of the Tribe and direct the Secretary to negotiate with the Tribe to determine the appropriate funding level for the contract.

Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act

In 2015, the Section 1121 of the FAST Act authorized the establishment of the Tribal Transportation Self-Governance Program (TTSGP) in the Department of Transportation. This authority provides federally recognized Tribes and Tribal organizations with greater control, flexibility, and decision-making authority over federal funds used to carry out tribal transportation programs, functions, services, and activities (PFSAs) in tribal communities. The TTSGP also affords Tribes and Tribal organizations with specific rights and federal resources to implement and support their Self-Governance programs.

Maniilaq Association v. Burwell

Court required the Indian Health Service to negotiate lease compensation under Section 105(l) of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act and implementing regulations for a proposed lease of Maniilaq Association’s clinic facility in Kivalina, Alaska.

Farm Bill of 2018

Section 4003(b) of the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-334); the 2018 Farm Bill) directed the USDA to establish a demonstration project for one or more Tribal Organization(s) within the FDPIR to enter into self-determination contracts to purchase USDA foods for their FDPIR program.

Section 8703 of the 2018 Farm Bill permits the Secretary of Agriculture to carry out demonstration projects by which federally recognized Indian tribes or tribal organizations may contract to perform administrative, management and other functions of programs of the Tribal Forest Protection Act through negotiated agreements entered into under ISDEAA.

PROGRESS for Indian Tribes Act

In 2020, the Practical Reforms and Other Goals to Reinforce the Effectiveness of Self-Governance and Self-Determination for Indian Tribes Act was enacted. The Act streamlines the U.S. Department of the Interior’s process for approving self-governance compacts and annual funding agreements for Indian programs and aligns the process used by the Department of the Interior to be similar to the processes used by the Indian Health Service.